THE PROJECT

Maria Papadimitriou

ΦIRMA GYPSY GLOBALES

The dress of the Gypsies (Roma) can be the vehicle for an anthropological and sociological investigation of a way of life whose most prominent characteristic is movement and non conformity to a dominant order.

The Gypsy people have long been scattered throughout Europe and have to this day preserved their autonomy, living in closed nomadic groups that rely on a heightened sense of tradition in matters of identity, dress, physicality, sexuality, material culture, family and relations between genders.

Today a series of economic and social shifts have been the cause of widespread déclassement (a form of downward social mobility) among social groups, the result of which is a class diaspora analogous to the nomadism of the Roma that has ensured their survival to date.

The activities of ΦIRMA GYPSY GLOBALES help reconstruct the history and genealogy of a Gypsy fashion house (whose ‘founders’ we follow from early twentieth century Romania to France, Italy and, lastly, Greece). The brand designs and manufactures lines of accessories, apparel, and objects which are represented alongside actual objects used by the Gypsies in their attire as symbols of the rituals that inform the tribe’s laws and relations, setting behavior patterns and determining cultural and aesthetic representations of the body.

Thus, a hybrid narrative device develops to explore issues of individual and collective identity, and explain the importance the Gypsies attach to their attire as a thing that singles them out visually.

ΦΙRMA GYPSY GLOBALES is a comment on the notions of appropriation, displacement, inauthenticity, copying, mimesis, and variation. It also proposes an interpretation of the constant transformation of symbols and life practices, alongside such contemporary trends as reusing and recycling.

The project includes the publication of a special edition which archives all relevant anthropological and historical content and is interspersed with instances of artistic reappropriation.

THE COLLECTION

Maria Papadimitriou

ONE – THE GOLDEN TOOTH

The habit of Gypsy men and women to file down their healthy teeth in adolescence and cover them with golden caps is not about their views on oral hygiene. It is all about ‘doing their own thing’, as they state to those who ask them today. Gold teeth form part of their ideas about wealth. It must be movable, just as they are, and becomes a physical affair, a part of their existence that distinguishes them from others, the strangers in their race. At the same time it makes them part of their group; it makes them true to the age-old laws of their own tradition.

Maria Papadimitriou

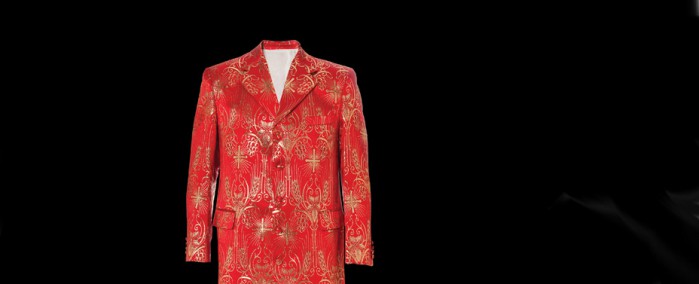

TWO – THE COSTUME OF YORGOS MAGAS

Yorgos Magas is a cult persona beyond the concept of a music idol, having acquired a reputation as an artist with metaphysical gifts. He is a self-taught clarinet player who embellishes his playing with jazz improvisations.

This ‘shaman’ of music pays special attention to his choice of costume for a performance. Every one of Mangas’ striking outfits stands out for its decorative elements and stylistic excesses that hover between glamour kitsch and ethnic baroque.

The outfit for the destefashioncollection is made of hieratic garments of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In liturgical vestment tradition the red colour is semantically charged by its association with the Byzantine imperial court. It is reserved for specific occasions such as the days of martyred saints or the morning of Holy Thursday.

Throughout their history, church vestments have retained certain standard traits that set them apart from the garments of other social groups. Their main unchanging attribute is that they are designed to hide the human body as much as possible: the excessive length and the long, narrow sleeves of the inner garments, the absence of any visible belt and the simultaneous use of several overlaid pieces have contributed to this from Byzantine times to this day. These sartorial choices that conceal the body are probably associated with the clergy’s wish to steer away from all material things, even from their own human nature, in order to get closer to the Divine.

The Gypsy musician appropriates the symbolism of ecclesiastical clothing, adapts it to the norms of Western male attire and uses it as a tool for the attribution of his own metaphysical worldview.

Maria Papadimitriou

THREE – THE GOLDEN VASE

If houses are the “vessels of life”, according to architect Aris Konstantinidis, to Gypsies the symbol of their own nomadic and traditionally homeless life is the vase. It is one of a Gypsy family’s few material possessions and forms part of their wedding ritual. The morning after her first night as a wife, the newlywed woman fills this vessel with water, takes a glass and goes to ‘refresh’ the male chiefs of other families. Having taken the glass of water from the bride’s hands, the chiefs kiss her and throw something gold into the vase.

Maria Papadimitriou

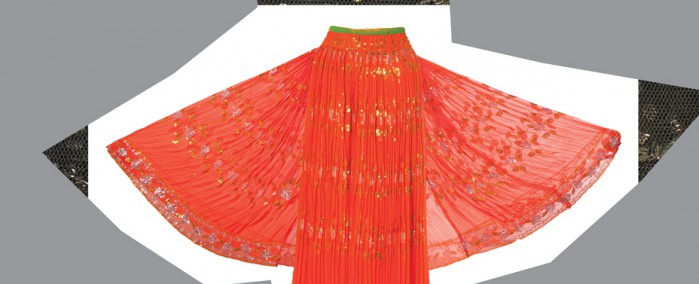

FOUR – THE SKIRT (ROTKIA), SCARF AND UNDERGARMENT

Gypsy attire is a female affair. The main element is the ample, long pleated skirt made of a thin, vividly coloured fabric with printed patterns. Purple, green, fluorescent orange with gold and silver, yellow, white over red or green over orange are the usual colour schemes for the skirts of all women, irrespective of their age. The apron (katrintsa) and a scarf (diklo) with coins or lace tied around the neck complete the main elements of Gypsy style. The skirt is fastened in front and the —narrower— apron falls over it and is tied in the back.

Various aspects of social life revolve around the semantics of the gypsy skirt. From the purchase of the fabric, the arrangement of the pieces and the sewing up to the offering as a ‘gift’ to a close relative or the accumulation of skirts as the dowry of a family’s girls, the skirt (rotkia, in the language of Romanian Roms) reflects women’s relation to their body. At the same time, it is the symbol of female authority, as the garment that covers and protects what Gypsies believe to be the impure area of female genitalia. The skirt thus stigmatises anyone who touches it. In Gypsy tradition, when a woman wipes her face in her skirt and then throws it at any man, even her own child, it is seen as a curse, the cycle of which can only be resolved with fire, while those stigmatised are ousted from the community and live on its fringe.

Gypsy strains from Eastern Europe and Turkey have one more garment in their sartorial vocabulary, a loose-fitting undergarment called sosten in the Romani language. This particular example comes from the Gypsy settlement of Aliveri, Volos. Its former owner, Marianna, believes that bloomers must be ample so that none of the female body’s erogenous zones are touched by the fabric.

Maria Papadimitriou

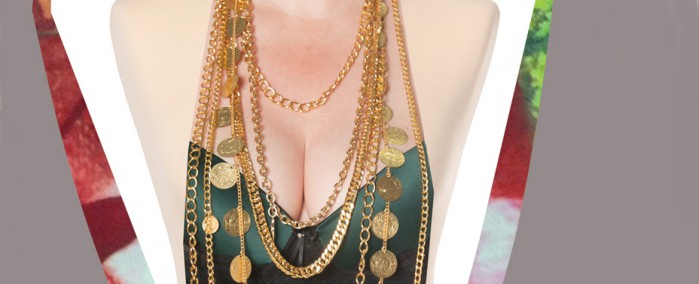

FIVE – THE GOLD JEWELRY

Gypsies do not live for money. They see it as the means to having a good life. Not familiar with the concept of preparedness, they do not save money. Nevertheless, they do have a special relation with gold. Gold chains and earrings are adorned with sovereigns to enhance female beauty, while the men will often sacrifice a sovereign to make rings. In any case, they carry their wealth upon their person because no one place is ever enough for a Gypsy, and group migration means that the nomads’ caravan must have light equipment and few possessions. Something in gold is always handy for survival, even in modern societies dominated by monetary union and the abolishment of currency fluctuations.