Patrizia Cavalli

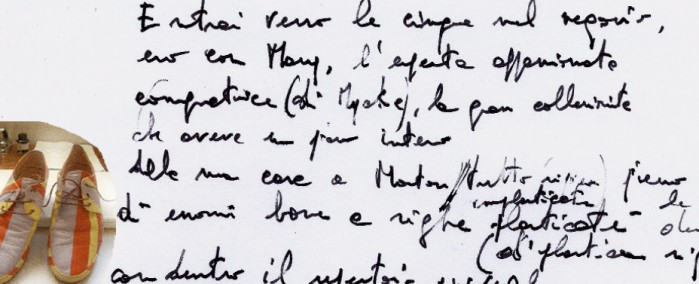

DANCING SHOES

Object: ISSEY MIYAKE shoes from Patrizia Cavalli’s personal wardrobe(2002)

I entered the store at about five, I was with Mary, the expert impassioned buyer, great collector, who had a floor of her house on Morton full of enormous checkered plastic bags containing, all tangled, the entire repertory of Miyake. It seemed a cemetery crowded and forsaken. But if you opened them the bags came to life: those little rags, compressed corpses, often moth-eaten, now resurrected to their original shape, Mary looking at them held them to her chest, played with them a little, warmed them, and the lucky ones, for two minutes at most, she wore. Then back they went— bye-bye. What more could you do— there were too many. But some of them at least lingered in the eye.

Collecting? Collections that democratically welcome all, as long as of the same kind? Comprehensive and charitable? Unwieldy and distracted? No, I collect nothing. Collections make me suffer—those kept spirited away, that you never get to see, and those always in clear view, that you no longer see.

All I wanted was a pair of shoes, the shoes that on the previous day, at closing time, I’d seen through a store window, and that no price, even the most impossible, would have discouraged me from buying. Those very shoes. Lavender, Amalfi lemon yellow and fresh rust, in wide irregular stripes—Pontormesque. Even just looking at them from afar I felt an aristocratic tremor in my feet rising up my legs and up some more, up, to my shoulders, traveling to my nape, circumvoluting my head, and sinking back down the front of me, irradiating the heart. Shoes that make a similar round can’t be ordinary shoes!Knowing where I was headed, my friend Mary had rushed ahead of me: “You’re not going to play with my toys without me,” she’d said. God forbid. So there we were, arm in arm, crossing the threshold. But as soon as we’d gone in I stepped away from her: I was bent on reaching the thing that had become lodged in my head while my energies were still intact, and I feared Mary’s obstructing extenuating delays as she prepared to browse through shelves and displays in the recalcitrant listlessness that always preceded her most intractable acquisitive sprees.

A salesman approached me: no sooner had I pointed to the object of my impatience than he was on his knees tendering the right shoe in the right size. How invigorating and reassuring to feel the laces tightening! The salesman pulled on them with such firm persuasion that, when he tied the final knot, my feet, tingling with joy, started wandering about in a festive dance that casually spread a little to the left, a little to the right, till it reached the mirror. Coming to a full stop I said, “I’ll take them,” and a rueful peace descended on us, or at least on me. Here I am, I thought, with these lovely shoes— they’re mine, I had them on my feet, I even danced in them—and instead of staying in that pleasure, staying in it at least till bedtime, I took them off and had them put away, shut away, into a box. O, why is one never prepared for palpable happiness? By what horrible timidity, silly bashfulness, or lousy indolence, do we pull away from the object of our love, from its breathless glee, and only after having subjected it to the trial of distance and privation, do we admit it once again into our midst? What is that conscientious desire which to pleasure’s naive and gluttonous impatience would antepose the quiet ceremony of possession? What was being staged—a wedding? Or an engagement from bygone times? I was steeped in these near-thoughts, more akin to a twisted embarrassment than to distended reasoning, when the salesmen, handing me the shoes, all wrapped up, bowed and said:

“This is a gift from the store to you.” “Really?” I said, my eyes wide. “Yes, please! This is a gift to you from the store.” “Do you really mean it?” “Yes, please. Please!” he repeated, repeating his bow. “Well, thanks then… thank you! How magnificently kind of you!”

Did I believe it? Yes and no. On one hand, it was obvious those shoes belonged to me by right: and I hadn’t spared my praises and exclamations. And wasn’t it after all in their tradition to offer what the guest admired? They might have thought it crude that I should pay for the shoes. It could be. But it might also have been a more indirect, more elegant way than a normal discount to gratify my friend who spent mad sums at that store. I approached Mary for an explanation:

“They want me to have them as a present… how come?” “What are you talking about?” she replied distractedly, her gaze shifting in every direction. “The shoes… they want to give them to me.” “Just take them then! Aren’t you pleased?” “And how! But why are they giving them to me? Isn’t it strange?” “It’s nothing to them! They can well afford it.”

“They’re doing it for your sake, that’s clear! A kind of bonus… a percentage on purchases. You already knew about it—tell the truth!”

“Not at all! But I’m not surprised. The truth is they’re fed up with Upper East Side ladies… all alike! They’re bored, and when someone like you comes in, dancing, even, it’s such a relief for them to break the routine! They see you, see the grace and geniality, the extravagance, inventiveness, energy, enthusiasm, and immediately they’re overcome with the desire to offer a gift. Poor things, they, too, have to have some fun now and then!”

I found the explanation convincing, even, I should say, definitive: so all that was left for me to do was go home and boast, especially considering that seeing Mary’s arms weighed down with merchandise—she was not in the habit of pointing to things: she touched, grabbed and clutched—I might have grown queasy had I stayed.

“Take a look,” I told my hostess, producing the shoes, “I got these as a present.” “Who from?” she asked, amused. “The store.” “Come on!”

“I’m telling you, I got them as a present.”

“O for God’s sake! They don’t give anything anyway. It must have been Mary.”

“No, I swear: the store gave them to me. They do that now and then when someone they really like comes along!”

“Forget it! They don’t do anything out of like. They never give presents. They wouldn’t give you a paper tissue. Mary must have payed for them, I’m sure.”

Even had it been true it wouldn’t have dimmed the pleasure of owning the shoes. But the boastfulness that had propelled me home, the certainty of having deserved those shoes solely for having, when I put them on, moved my feet in a jig, began to waver: it was no longer a public gift for obvious merit, but a private gift, made out of personal affection. Soon I discovered that it was so. The following morning Mary admitted to having payed for the shoes, she admitted it right away, because, she said, it was clear how things stood. It was the salesman’s fault—he had played his role badly: he’d been awkward and hurried whereas he should have presented the gift along with a series of irrefutable arguments, following Mary’s meticulous instructions. Unfortunately he wasn’t the right salesman, the right salesman wasn’t there that day, and she was really annoyed.

I’ve had those shoes for ten years. They look new. And though they’re very comfortable, I wear them only on special occasions, though I wouldn’t know what those might be since usually I expect the occasions themselves to put themselves forward, there and then, as special, which, truth be told, they rarely do. I don’t mind that because the less I use them the less I can get used to them, and never would I wish to get used to them. How sad the day when I might no longer be surprised by those extreme unexpected colors, by that preening squealing yellow! And what melancholy if I stopped delighting in their form, its mannerist grace, that tenderly yet firmly envelops my feet and lends my feverish boastful steps the levity of goodness that they might reach their destination without much clamor, floating, almost.

Patrizia Cavalli

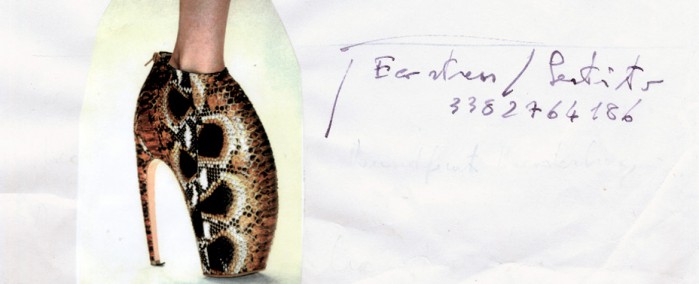

IS WALKING REALLY NECESSARY?

Object: ALEXANDER McQUEEN “Armadillo” python shoes (Spring/Summer 2010)

From a grave imperial immobility comes the question: “Is walking really necessary?”

I say: “No, and as for running even less so. With you, it’s clear, one cannot rush. You are ecstatic shoes—honeycombs, trophy cups, wherein, interred bulbs, remain enclosed stings, languors and quivers, sweetnesses and vanishings: something that conceals and detains, from which firmly rise two stalks that at the top are joined in flower.”

“Keep away, Earth—gravity offends us, we are distance itself, the vertical unravelling of a dance.”

“It’s true: since Celestial Empires never had been seen a foot so nil then magnified into a balletic back, bulging back rounded pregnant belly. With you anyone dances standing still.”

Patrizia Cavalli

CARAVAGGIO – A JACKET FOR CHEATS

Object: DIANE DE CLERCQ “Caravaggio” lambswood knitted jacket (Winter 2010)

You’re going to wear this jacket every day until somebody says, “You’re cheating!” And then but only then you’ll put it away.

Patrizia Cavalli

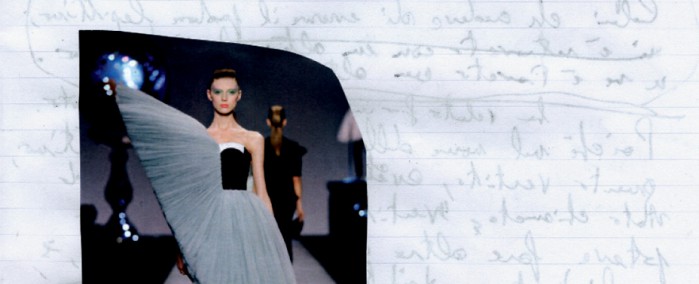

DETACHMENT DRESS

Object: VIKTOR & ROLF “Look 36” dress from the Cutting Edge Couture, Collection 27, (Spring/Summer 2010)

Descending from on high, I’d sunk down into a big rich dense crinkly soft hut of angelical turquoise. Then what happened? A piece of it was cut. But I was so distracted I never realized: it slid down and by some spell there it stayed solid and still, it cannot go up any more, cannot fall down any lower, it stays where it lays, in my Part Two—counter-tutu. Remote and nonchalant, since it’s there, I take it out on walks, like an adolescent in low-slung pants. But where do I fit in? What am I to do all the way up here, in my tutu?

Tutu—countertutu. Matter—antimatter. And in between a blank space with a core even blacker. I have on my detachment.

Patrizia Cavalli

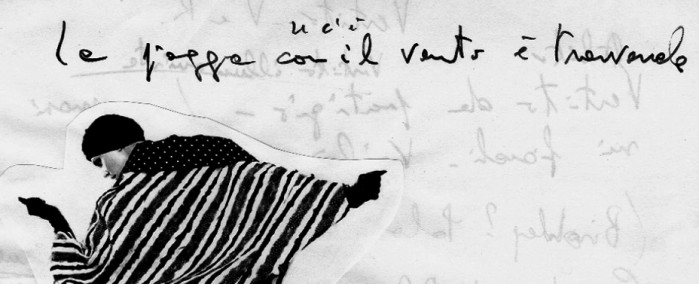

FEATHERED, AT A SLANT

Object: STEPHAN JANSEN “Cerf Volant” cape (Fall 2010)

When there’s wind the rain falls slanted. Dampness threatens, and the heart’s exposed.

But give me a slipcase one made of feathers and slanted stripes!

I wiggle my behind like a duck — I’ll be upright, impermeable, intact.

Patrizia Cavalli

HUMORAL PARABOLAS

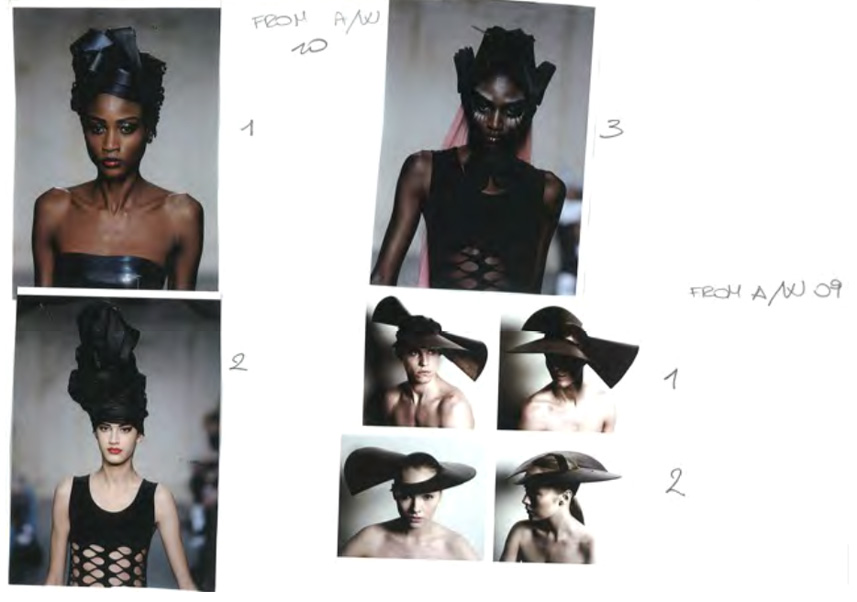

Object: NASIR MAZHAR leather hat (2009)

About those brims, ellipses or parabolas, the one thing certain is they’re no use against the heat or against the cold and weren’t meant even as ornament since that as such would let itself be bent to individual taste perhaps —not so rigid, so unbending a tyrant it may not be moved even an inch, but inclined, rather, the shiny mighty warrior, to lead us all to war, though not now, and not on this earth. So if this parabolical matter truly hath nothing of the hat, and is no use, even as ornament, then what is it for? It’s obvious: it’s there to spin along its double sapiential ring the fatuous little sirens of the mind which in a wavering endless to and fro from the brain’s within to the great outdoor, move from us to the sky, back and forth, in their humoral not knowing whether the Mahzar on your noggin was designed for taking or for giving, for receiving or for sending, or the two of them together and all at once. Human, as we know, is flamboyance.